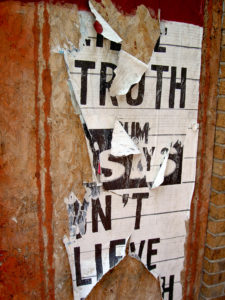

The two words are not synonyms. The difference between them is important, especially in our post-truth world.

The definition of the adjective post-truth, the Oxford Dictionaries 2016 word of the year, shows how “truth” and “facts” have become muddled.

For example, back in the early days of TV, Dragnet’s Sgt. Joe Friday and others craved “Just the facts, ma’am” in order to get to the truth. (By the way, according to the Snopes fact-checking site, most people misquoted the detective. Sgt. Friday actually said “All we want are the facts, ma’am,” which attests both to our faulty memories and often our insistence that we are certain when we’re not.)

Now in our post-truth world, many of us find appeals to our emotions and beliefs sometimes more compelling and influential than facts in shaping what we think, trust, and accept as true.

Also, when we’re in a hurry or upset with someone or a situation, it’s also easy to swap “truth” for “facts” or vice versa.

Nonetheless, for anyone who wants to practice critical thinking or be considered trustworthy to others, you need to know and practice the distinctions between “facts” and “truth.”

For example: We check facts and seek our truths.

Or to view it another way, you speak truth to power. You don’t substantiate the truth; instead, you respect it and try to understand it. And you may not even be able to handle the truth as Jack Nicholson’s character barked in the 1992 movie A Few Good Men.

A fact is something that is indisputable that you can verify. Until proven wrong, a fact will stand as something that exists, happened, or occurred.

Facts include the following: Jeff Bezos is the CEO of Amazon.com. The company was founded in Seattle in 1994 and debuted on the Web one year later. Amazon.com announced in 2009 it was buying online shoe retailer Zappos and in 2017 healthy grocery retailer Whole Foods Market.

By contrast, the truth is subjective and reflects beliefs and feelings. It varies by person, and can even change for a person. For example, one of my truths today is that I love buying books from Amazon.com. But that may not always be true, especially if Google or someone else gets into the book selling business and convinces me to change my allegiance.

Yet, if you judge my truth about Amazon.com or any other truth I hold – even if it’s probably erroneous, such as my belief that gelato is a healthy food choice for summer lunches — you run the risk of losing my respect in you.

That’s because my truth is related to my experiences. In the gelato example, I’ve enjoyed gelato, ice cream, sorbet, popsicles, and other frozen novelties for lunch many times with no adverse effects that I’m willing to admit. I want and expect you to respect my truth – maybe not necessarily this one but certainly others that are more consequential for me.

If you are judgmental about my truth or any other person’s truth, you can erode trust, explains Mary-Frances Winters, author of the valuable new book We Can’t Talk About That at Work! How to Talk about Race, Religion, Politics, and Other Polarizing Topics.

To maintain or try to build trust, you need to sort out the facts from the truth for yourself and those you work with and especially lead. That can help you find common ground rather than create a wedge that will drive you apart.

Being clear – not necessarily certain – about the differences between facts and truth can help you better adjust to a polarized post-truth VUCA world.

What’s your truth?

0 Comments